By Jennifer Borland

Reposted from yourevalpal

Over the course of the past three years, I’ve had an opportunity to study and evaluate digital learning programs offered by the Smithsonian, and the Smithsonian Center for Digital Learning and Access – including a series of online conferences and a digital badging program called “Smithsonian Quests.” In preparation for a presentation on behalf of the Smithsonian to share my collective findings from these research efforts, I thought I’d summarize some of the big take-aways from these studies here.

About the Programs:

Online Conferences The online conferences offered as part of the Smithsonian’s Expanding Connections grant program provided opportunities for teachers and students to interact with Smithsonian staff and expert guests as well as fellow conference participants from all over the world. The 2013 and 2014 conference line-ups included a diverse mix of topics designed to engaged teachers and students. Attendees during the live conference events had an opportunity to interact with the presenters and other participants. Others, including those who presumably were unable to attend the live conference events, are able to view archives of the conference sessions posted online after each event.

Digital Badging Program Smithsonian Quests invites users to create an account and complete a series of quests to earn badges on a variety of different topics. The quests invite participants to explore Smithsonian resources, gather information from many different sources, and to employ 21st Century skills such as critical thinking, creativity, appropriate use of technology and communication skills. The number of available quests and corresponding badges, has continued to increase over time, and has expanded to include quests in various subject areas including science, history, civics and social studies.

Methods

Each year, and collectively over the course of the past three years, we have asked the following questions:

- What factors contribute to or hinder the success of the programs?

- Do the programs adequately encourage and incentivize participation?

- Is there evidence of sustained participation?

- How does participation in one program correlate to participation in other Smithsonian programs?

- What are the learning and behavioral outcomes that result from participation in the programs?

To answer these questions, our evaluation effort has included participant surveys, observation and assessment of online sessions and submissions, informal participant feedback, and regular conversations with members of the Teacher Advisory Group responsible for reviewing participants’ submissions on the Smithsonian Quests site. Also, to evaluate the relative quality of quest submissions, we established and implemented a basicevaluation rubric (also used by members of the Teacher Advisory Group during their assessment of quest submissions:

1. Is it Complete? Did the participant complete all of the required tasks? (If no, provide some feedback about what is missing).

2. Is there evidence of Content-Mastery? Does the submission indicate that the participant has learned what the quest was intended to teach? (If no, provide some feedback about what is missing).

3. Is there evidence of broader Connections? Does the submission show evidence of how new knowledge has been integrated or connected to other knowledge? Is there evidence of deeper insights or further thought about the topic? If yes, make an effort to recognize instances where participants have made more connections and made a greater effort to synthesize content from the quest.

4. Is there evidence that the participant took extra Care or exerted a great deal of effort in completing his/her submission? This final rubric question was added because we felt that quests that suggested that a great deal of time and effort had been made were deserving of a few extra accolades.

Findings from our Evaluation of the Online Conferences

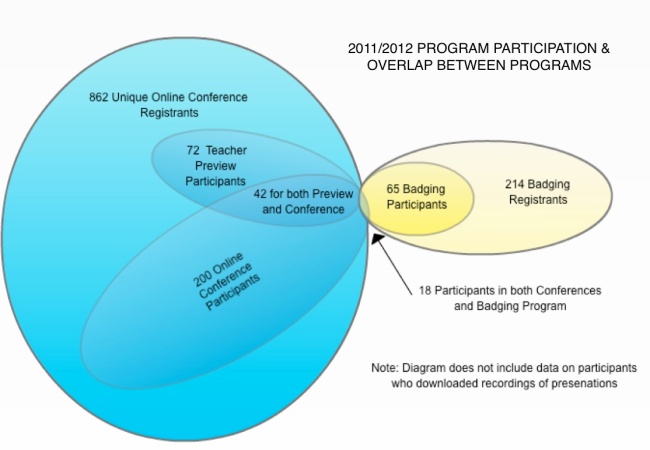

During the first year (i.e., 2011/2012 School Year) we found participation in the conferences to be much greater than participation in the newly launched badging program. Despite efforts to heavily cross promote the two programs, we didn’t see a lot of overlap in participation – in fact, of the 1050 unique participants* in the program over the course of the year, there were only 18 who had actively participated in both programs. *It is important to note that we have seen evidence to suggest that there are significantly more student-participants for each registered teacher-participant, so the reach of these programs goes much farther than merely those participants who register.

Our evaluation of the online conferences included a content analysis of the dialogue that took place between conference presenters and conference attendees. We found that communication typically fell into one of four categories:

- greetings (i.e., when participants said “hello” and stated where they were located),

- resource and information sharing,

- questions (typically directed toward a presenter – and later subdivided into the following three categories: 1) Personal, (i.e., questions about participants’ own experiences), 2) Knowledge, (i.e., questions that sought to determine what participants knew, or didn’t know, about a particular topic), and 3) Exploratory (i.e., questions that sought to explore thoughts and beliefs about topics or to start a discussion), and

- answers (usually in response to a question asked by a presenter).

Creating the right environment for interaction Questions, and the resulting answers, comprised the vast majority of communication during conference sessions, and that is where we subsequently chose to focus our attention for further analysis efforts. For each session, we generated a data set that included the number and types of questions asked, and the number of responses. Generally speaking, higher numbers of presenter polls and questions tended to correlate with higher numbers of participant comments and questions. An average of 12-15 questions—including a mix of polls (with multiple choice response options) and open-ended questions, seemed to be sufficient for an hour-long presentation and still allow enough time for presenters to answer questions posed by participants. However, it was presenters’ responses to participants’ questions that seemed to be most important in setting a more interactive tone for the presentation. The hosts from Learning Times and the Smithsonian played a critical role in helping to draw attention to participants’ questions and work them into the conversation in a timely and efficient manner.

Live participation affords more benefits Data indicates that the live-conferences were seen as slightly more valuable than recordings of the conferences, likely due to the ability to interact with expert presenters, which participants indicate is very important. Unfortunately, not all participants are free to participate at the time a live conference is offered, so the ability to access archived recordings of conference sessions is a valuable resource for learners and educators.

Interacting with experts, others is engaging We found that the conferences allowed youth to become more engaged in topics by interacting with experts and other participants in online conferences. It was inspiring for students to see people from all over the world participating in collaborative learning opportunities. Likewise, it seemed to be validating for educators to see peers participating in similar types of digital learning programs.

Findings from our Evaluation of the Digital Badging Program

Participation in the badging program increased rapidly during its first full year. When we first reported on the digital badging site, just a few months after its launch in the Spring of 2012, there were only 18 participants who had completed badges (and collectively they had completed a total of 76 quests). As of December 13th, there were 1489 active participants (and more than 3000 members registered for the program) and 3077 quests completed.

Participant-Level Findings and Outcomes

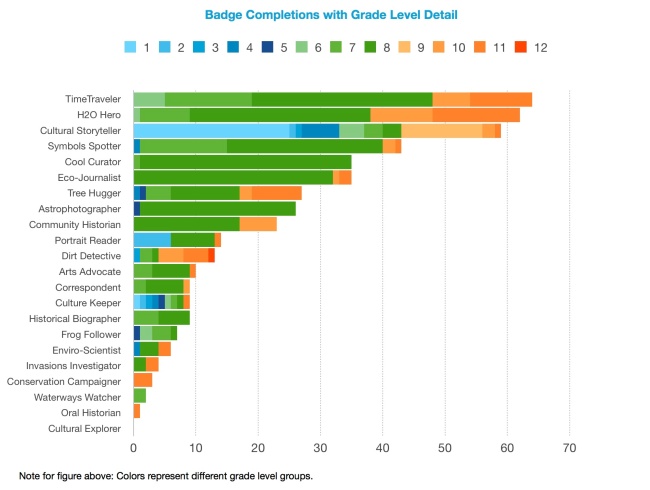

Patterns of participation across time and grades The Smithsonian Quests program is flexible enough to be use successfully at a variety of grade levels and with students of different ability levels. None-the-less, we saw distinct patterns in which badges were at each grade level. Overall, the middle grades, e.g., 4th-9th tended to be most active, while the lower grades and higher grades were more sporadic in their use of the Smithsonian Quests site. Use of the site by students in higher grade levels seemed to pick up toward the end of the school year.

Unique opportunity for student expression The Smithsonian Quests program fosters a variety of skills including researching, writing, and using technology. Teachers often voice concern about how hard it is to get their students to write, but members of the Teacher Advisory Group indicated that Smithsonian Quests provides a unique opportunity for students to express themselves through writing and other forms of communication. Participants’ submissions include many examples of work that clearly goes above and beyond the stated goals of the quests and demonstrates a much higher level of care and effort (i.e., the fourth criteria on the evaluation rubric that we established).

Fostering self-motivated learning Teachers commented about the potential appeal and value of the program beyond formal classroom settings (e.g., in scouting programs or for self-motivated learning). This is evidenced by the fact that submissions continue to come in over the summer months, and suggests the appeal of the program beyond formal educational contexts.

Educator-Level Findings and Outcomes

Challenges and barriers to participation Educators have a lot of demands for their time and attention. As such, the biggest challenge or barrier for participation seems to be “time,” i.e., the time necessary for teachers to explore the site, familiarize themselves with the resources and activities, and plan for ways to most-effectively involve their students in the experience. There were many educators who registered to participate in the Smithsonian Quests program with the intent of coming back to the site and spending more time exploring, but ultimately found that that time never came. To keep the site and its resources in educators’ minds over time, it may be helpful to send periodic communications to registered educators – with tips for how to integrate activities, short articles that highlight new activities or quests, and stories of exemplary outcomes from actual participants. Access to technology has also posed a challenge for some educators, but takes a back-seat to the barrier of the initial time it takes for teachers to do all the back-end work required to ensure a successful digital learning experience.

Variety is the spice of digital learning Through surveys and interviews, educators have stressed the importance of having a wide assortment of quests that will appeal to different types of learners and meet the needs of different types of educators. In all cases, however, educators stress the need for there to be clear curricular connections within each quest. The variety of quest topics, activity types, and corresponding resources is clearly among the greatest strengths of the Smithsonian Quests program.

In-class supports are still an important part of a successful digital learning experience Teacher Advisors for Smithsonian Quests were quick to point out instances where participants appeared to have less in-class supervision and support. Students in these groups struggled in their efforts to successfully complete quests because their work did not appear to be monitored, reviewed, or scaffolded in any way at the classroom level. Even with a robust and well-designed digital learning experience, the role of a classroom teacher or other on-site facilitator is still paramount to a participants’ ultimate success.

Other Resources Related to the Evaluation of Digital Badges

Hickey, D. (2013) Research Design Principles for Studying Learning with Digital Badges: http://www.hastac.org/blogs/dthickey/2013/07/07/research-design-principles-studying-learning-digital-badges

Schwartz, K. (2014) What Keeps Students Motivated to Learn?: http://blogs.kqed.org/mindshift/2014/03/what-keeps-students-them-motivated-to-learn/

Sullivan, F. (2013) New and Alternative Assessments, Digital Badges, and Civics: An Overview of Emerging Themes and Promising

Directions http://www.civicyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/WP_77_Sullivan_Final.pdf